Hiram was born in the Netherlands in 1854.

His first article, Hiram Bauke Ferverda (1854-1925), Part 1: Baker’s Apprentice chronicled his life in the Netherlands.

In 1868, at age 13, Bauke immigrated to the US with his family. His life after immigration, as a farmer in Elkhart and Kosciusko Counties in Indiana, was documented in Hiram Bauke Ferverda (1854-1925), Part 2: American Farmer.

Part 3 begins with Hiram’s move to town and new career, beginning at age 54, and takes several entirely unexpected turns. You might want to make a cup of tea, because this one is both fascinating and long. It’s amazing what you can find in local newspapers that allows us to time travel and visit our ancestors in the time and place where they lived.

I must say that I had NO IDEA of most of the events that both influenced and changed Hiram’s life before I mined the newspaper articles. This man was alive 100 years ago, so I thought I knew about him through my family, but I didn’t. I would never have expected many of these discoveries because of his Brethren religion, but here they are, in black and white. A complete dichotomy.

I feel like I actually know Hiram today – and I thought I knew him before but all I had was a sketchy outline, a couple fuzzy stories and a few paragraphs in a book.

- Hiram both upheld the law and broke the law.

- Hiram eschewed violence but was a lawman.

- Hiram was a pacifist, yet 4 of his sons proudly served their country.

This man was a study in opposites and perhaps in conflict as well.

Come along on Hiram’s amazing “second act” journey!

The Move to Leesburg, Indiana

In 1908, Hiram’s life took a dramatic change – and not one you’d expect for a farmer and certainly not for a farmer past the half century mark.

Hiram moved to town. Not a big town, but Leesburg with about 800 people, the closest town to his farm – more like a village. Hiram gave up farming, with his son moving to his farm and taking over day to day operations.

According to the Ferverda booklet written in 1978, Hiram supervised the laying of the brick streets in Leesburg which vehicles still drive on every day. I visited Leesburg in May of 2019 and found those same brick streets which remain beautiful, a tribute to his work more than 100 years ago.

![Hiram-Ferverda-brick-prairie-street.jpg]()

Prairie Street in Leesburg, Indiana

Hiram became a director of the Peoples State Bank in 1908 and later Vice-President. Yep, he became a banker. Farmer to banker – now THAT’S a career change!

Son Donald Ferverda became Cashier a decade later, after his high school graduation, and eventually Director before his untimely death. In later years, another son, Ray Ferverda, became a Director and Vice-President as well.

It’s unclear where the actual bank property was located, although it may have been where the Freedom Express office building is found today.

Hiram’s Property

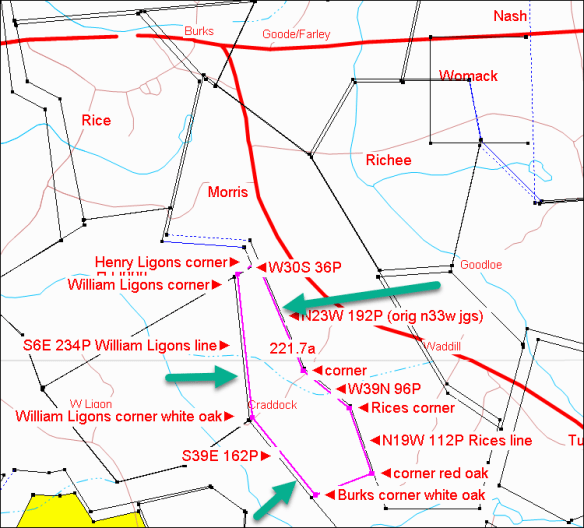

Hiram owned the entire section between Main on the west, Church on the south, the right side of this graphic and the alley between Church and Prairie on the north.

![Hiram Ferverda google map Church Street.png]()

Today, that’s the gas pump area of the Freedom Express convenience store and gas station – along with the lots to the right along Church Street.

Note that in this aerial, you can still see the red bricks on Prairie Street. It’s possible that Hiram owned the area noted with the Freedom Express too. The deeds are not clear.

![Hiram Ferverda google map Church Street aerial.png]()

The Kosciusko County Surveyor’s office was extremely gracious, providing me with the 1938 flyover image of these properties.

It’s possible but uncertain if Hiram also owned the top portion of the lot, now 201, then referred to as 117, that includes the Freedom Express building itself today.

![Hiram Ferverda Church Street 1938 flyover.png]()

These images are grainy and difficult to see, but we can discern structures.

The deed for this property is confusing. Between the Auditor’s office, the Recorder’s office and the Surveyor, I think we have it straight.

![Hiram Ferverda 1909 deed.jpg]()

The problem begins with the fact that the lot numbers given in the deed are not the same as the lot numbers today. To help map this, a rod equals 16.5 feet.

Lot 117 was originally what is showing today as both 201 and 205, which provides us with a place of beginning and is shown on their GIS system below.

![Hiram Ferverda Leesburg GIS.jpg]()

However, based on the deed metes and bounds, lot 117 does NOT appear to encompass both 201 and 205, only 201. There was some confusion about this when I was in the Recorder and Auditor’s offices too. Based on the metes and bounds, it appears that lot 117 incorporated 201 and lot 116 incorporated 211 and possibly 209/207 as well. Perhaps lot numbers has not been assigned to 205, 305, 208 and 206, the properties it appears that Hiram owned.

201 and 205 are addresses today, on Main. 305 is on Hickory. 206 and 208 are on Church and 207, 209 and 211 are on Prairie.

Based on the metes and bounds, it appears that Hiram owned the red area, 205 below, and not 201.

![Hiram Ferverda GIS land.png]()

One of the offices told me that lot 201 or 205 had been the Farmer’s State Bank before it was purchased for a gas station and convenience store. This building, below, on lot 201 would be the best candidate.

![Hiram Ferverda Lot 201.jpg]()

However, the most recent Farmer’s State Bank building was directly across Main Street from this location, so the person may have been recalling that.

![Hiram Ferverda Leesburg 1938 structures.png]()

In this 1938 flyover, we can see that there are two buildings on this group of lots owned by Hiram. One on the main property, at the left, and one on Hickory at the alley, which probably wasn’t Hiram’s home based on other evidence. I wish these were clearer, but it’s great to have anything from 1938. Eva would still have been living then, probably in this house. Maybe she was inside when the picture was taken!

Perhaps Hiram did not actually own the bank itself which could have been on lot 201, or even downtown. My brother John told me that Hiram and Eva lived “on the main road” which would reflect a house on the corner of Church and Main. In any event, today, I pumped gas where their house once stood – where my mother went to play as a child.

![Hiram Ferverda Citgo.jpg]()

This photo is taken from across Main Street, looking at lot 205. The convenience store part of the building, and the small office building facing Prairie behind the convenience store sits on lot 201 today.

![Hiram Ferverda 201-205.jpg]()

Hiram and Eva’s home would have been right about where that canopy shields people who pump gas today. I didn’t realize that when I was gassing up on “their” land.

![Hiram Ferverda 205 only.jpg]()

Looking down Church Street from the East end of Hiram’s property back towards Main, we can see that only modern buildings exist today.

![Hiram Ferverda Church street lots.jpg]()

No houses were present in 1938 except on 205, which had to be Hiram’s house.

Let’s take a look at Hiram’s life through the newspapers.

1908

January 11, 1908 – Warsaw Daily Times – Margaret Ferverda, who has been quite sick, is improving.

Margaret turned 6 on January 12th.

April 2, 1908 – The Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda April 1908.png]()

Hiram’s father, Bauke, known as Baker in the US, is Grandpa Ferverda whose wife had died in 1906.

Hiram Becomes a Banker

April 17, 1908 – Warsaw Daily Time

![Hiram Ferverda April 1908 banker.png]()

I can’t even begin to imagine what possessed Hiram to open a bank! It looks like the new bank was in the same building as an existing bank with the same people involved, given that Joel Hall is president of the new bank.

Brethren typically wanted nothing to do with government, nothing to do with “swearing oaths” or signing documents. Many deeds were never registered nor were licenses obtained for marriages in Brethren families. Even for a progressive Brethren, owning a bank was a huge step. Had I not known better, I would immediately eliminate the Brethren religion for any person owning a bank, being involved with government, law enforcement or warfare of any kind. This was very out of character and unexpected.

Hiram would die before the economic crash of 1929, and maybe that’s a good thing, because that might just have killed him. Banks didn’t fare well although this one survived.

And a Politician

June 2, 1908 – Warsaw Daily Times – Republican County Convention – Representatives if Party Assemble in Auditorium at Winona Lake and Choose County Ticket – (many names including) Plain Township – first precinct – Hiram Ferverda

Winona Lake is threaded throughout the news. Not only was it a recreational area, but many conferences were held there, making it a destination area throughout Indiana. Apparently, the Winona Lake region, located nearby, had facilities to handle, and house, crowds.

June 11, 1908 – Northern Indianian – Republican Convention held at Plymouth Indiana for congressional nominee. Speeches were given and the seat is contested. The convention is being held in the open air on the lawn of the old Henry C. Thayer property. Those Kosciuskoans who went to the Plymouth on the Pennsylvania train leaving this city at 8:20 a include…Hiram Ferverda.

Death is Ever Present

Especially in large families, death is an ever-present fact of life. Penicillin wasn’t discovered until 1928. People died then of infections and diseases that would be easily curable today.

October 22, 1908 – Hiram’s sister, Melvinda, died on October 12, 1899, leaving husband James Gibson and daughters, Minnie, Gertrude and Alma. James Gibson died on May 30, 1907, and daughter Alma died on September 10, 1908 of tetanus.

Hiram’s brother, William, became the guardian of both surviving daughters, replacing Peter Bucher, with Hiram posting his performance bond in the amount of $2000. Hiram signed this bond, providing us with his only actual signature.

![Hiram Ferverda October 1908 bond.jpg]()

I love Hiram’s signature, below that of his brother, William. He actually signed in two different places on that document

![Hiram Ferverda signature.jpg]()

Nov. 12, 1908 – Warsaw Daily Union. Marriage license issued to Rolland Z. Robison and Chloe Ferverda, both of Leesburg.

Rolland, known as Rollie, and Chloe would have an unnamed stillborn son in 1911, then Robert Robinson, Earl Robinson and Charlotte Robinson.

![Hiram Ferverda, Eva, Chloe, Margaret.jpg]()

This photo, brought to the 2010 reunion shows Eva, Chloe, Hiram, Margaret, Bob (Robert) and Earl.

Robert was born in 1913 and Earl in November 1916, so I’d guess this was taken about 1917 or perhaps 1918. Hiram would have been about 64.

Dec. 24, 1908 – Northern Indianian – H. B. Ferverda allowed $48.24 for the gravel road in Plain Twp.

1909

February 3, 1910 – Northern Indianian – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg was in the city (Warsaw) Thursday.

![Hiram Ferverda Warsaw courthouse.jpg]()

I visited the courthouse in Warsaw in May of 2019, knowing that Hiram would have been in this building many times, attending to business.

February 5, 1909 – Warsaw Daily Times – Samuel Ulery, George W. Cummings, Hiram Ferverda and Charles Matthews, of Salem and vicinity will all move to Leesburg.

Samuel Ulery was related to Hiram’s wife, Eva Miller, in multiple ways.

Hiram opened the bank in 1908 and moved to Leesburg a year later in 1909, probably to be closer to business affairs. As reported on the Farmers State Bank web page, local people and farmers had confidence in people they knew. I do wonder why these several families moved to Leesburg at the same time. Leesburg was then and still is small, the downtown extending all of a block.

![Hiram Ferverda Leesburg business district.jpg]()

I love the bricked-in windows that give us a hint of what these building used to look like.

![Hiram Ferverda Leesburg business district center.jpg]()

These old buildings speak of times that were. This entire business district is all of one block long.

![Hiram Ferverda Leesburg business district end.jpg]()

I’d like to know what these buildings where when Hiram lived in Leesburg.

![Hiram Ferverda Leesburg 1907 building.jpg]()

At the top of this building, you can see that it was built in 1907, so it was brand-spanking new when Hiram lived here.

One of these buildings was assuredly the Town Hall where Hiram would conduct many of his duties.

It seems that Sundays were church and then social days.

February 11, 1909 – Warsaw Daily Union – Hiram Ferverda, wife and little daughter Margaret were Sunday guests of Erve Ferverda.

Moved to Leesburg

March 10, 1909 – Warsaw Daily Union – Hiram Ferverda moved to Leesburg Wednesday and Thursday Erve Ferverda moved on the home place.

On March 19, 1909, Hiram bought the lots in Leesburg.

This seal in the old courthouse was probably used on many of Hiram’s documents, including his deeds.

![Hiram-Ferverda-seal.jpg]()

May 6, 1909 – Commissioners allowances to John Pound to view Ferverda road – $4.

This is an interesting entry, because no place else have I found mention of Ferverda Road.

1910

On the 1910 census, Hiram and Eva lived in Plain Twp., west of Big 4 which was the description for all of Leesburg. The railroad tracks ran just east of town, along “Old 15.”

![Hiram Ferverda 1910 census.png]()

January 27, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Times – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg was in the city (Warsaw) Thursday.

Feb. 3, 1910 – Northern Indianian – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg was in this city (Warsaw) Thursday.

The Paternity Suit

Feb 9, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Union – This would be Ray, not Roy. There was no Roy Ferverda that I’m aware of. Maybe Ray was pleased to be misidentified, all things considered.

![Hiram Ferverda Ray trial.png]()

This is a very suggestive entry in the paper which makes me suspect paternity. Rape would not have been a civil suit, although this does not say specifically.

![Hiram-Ferverda-courthouse-Lake-Street-door.jpg]()

The old courthouse doors still remain. Hiram surely accompanied his son to court.

![Hiram-Ferverda-courthouse-stairs.jpg]()

And climbed the stairs to the second floor.

On February 12th, the following:

![Hiram Ferverda Ray transcript.png]()

Confirming that the name is Ray, not Roy.

Sept 7, 1910 – State against Ferverda set for trial Sept. 23rd.

Aha, indeed, it was paternity! This means that there are potentially additional DNA relatives out there!

September 19, 1910:

![Hiram Ferverda Ray paternity.png]()

Typically, at that time, people in this situation married. I wonder why Ray and Lucretia chose not to. Or maybe, just one chose not to.

The 1910 census shows a Lucretia Brown, of the right age and location, but with no child.

![Hiram Ferverda Lucretia 1910 census.png]()

Did the child die? I didn’t find either a birth or death record. Perhaps placed for adoption? Being raised by someone else?

Lucretia married George Eldridge in 1914 and was living in Wabash in the 1920 census with two children, ages 3 and 4, but no child that would have been 10 or over. I wonder if an eventual DNA match will provide the answer.

The Great Bluegill Caper

I tried not to laugh at this, but especially given the earlier political commentary about the unfair fish laws – I just couldn’t help myself.

March 22, 1910:

![Hiram Ferverda bluegills.png]()

This incident was reported by the Warsaw Daily Union using exactly the same words, but with much larger headlines

Bluegills huh? I’m thinking there is more to this story that we will never know.

Cheryl told me that the edge of Hiram’s farm touched Lake Tippecanoe because Don or Roscoe fell through the ice at one point.

March 21, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Time

![Hiram Ferverda fined for fish.png]()

March 24, 1910 – Warsaw Union – It cost Hiram Ferverda $75 for taking 5 bluegills from Tippecanoe lake with a net. He entered a plea of guilty to the charge against him.

Also reported in the Northern Indianian, of course. This would have been great gossip!

I can just see Hiram’s teeth clenching!

Most expensive fish per ounce EVER.

![Hiram-Ferverda-courthouse-cupboards.jpg]()

Hiram would have passed these old cupboards in the Warsaw courthouse on his way to answer for his fish crimes. Maybe the evidence was even held here!

March 31, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Times – Rollin Robinson and wife spent Easter with the latter’s parents, Hiram Ferverda and wife of Leesburg.

July 7, 1910 – Fort Wayne Journal Gazette via a “special correspondent.”

![Hiram Ferverda July 1910.png]()

Mr. and Mrs. Hiram Ferverda spent the day with Mr. and Mrs. John Ulery of Nappanee who are at their cottage at Government point, at Tippecanoe Lake.

They may have had no idea they are related to the Ulery family through the Millers, because they are also related to the Ullery family through Eva’s mother’s first husband’s family. They are also related to the Ullery family because Eva’s half-sibling, Emanual Whitehead married Elizabeth Ulery and her half sister, Mary Jane Whitehead married John D. Ulery. Yes this is a family vine!

July 12, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Union – Mr. and Mrs. Hiram Ferverda attended church at Salem, Sunday and took dinner with their daughter, Mrs. Louis Hartman and family.

Sister-In-Law Dies

July 19, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Union – Hiram Ferverda received a message Sunday morning stating that his sister-in-law, Mrs. Fannie Ferverda died at her home near Nappanee Saturday evening.

This would have been his brother, William’s, wife.

While Hiram and Eva appeared to be quite social, there are surprisingly few mentions of Hiram’s brother and family. I suspect that part of this may be due to the fact that William’s side of the family appear to have remained more conservative in the traditional Brethren ways, while Hiram became increasingly progressive throughout his life. Distance was probably also a factor, although they clearly do keep in touch.

August 10, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Union – Boyd Whitehead of Goshen is visiting Hiram Ferverda and family.

Off to Kansas

August 18, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Union – Hiram Ferverda, Frank Bortz, Charles Dye and Henry Kinsey started on a 10-days pleasure trip for various points in Kansas Tuesday morning.

Then, later in the same article about Leesburg residents:

Mr. and Mrs. Hiram Ferverda were Warsaw visitors Monday.

August 25, 1910: Frank Borts II, E. Kinsey, Hiram Ferverda and Charles Dye arrived home Monday afternoon after a 10 day pleasure trip through Kansas and Colorado.

So, what happened to Illinois and Missouri?? What did 4 men do? I wish they had told more of the story!

Sept 23, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Times – Ulery Family Reunion – Descendants of Daniel Ulery Held Enjoyable Meeting at the Home of John D. Ulery – The descendants of the Daniel Ulery family met at the home of John D. Ulery at Government Point on Tippecanoe Lake Thursdays. Those present were: (long list including) Hiram Ferverda and wife of Leesburg.

I notice that Emanual Whitehead was also present. I thought perhaps that this would lend itself to breaking down brick walls, but one Daniel Ulrich was born in 1811 in PA and died in 1834 in Elkhart County, His father was Jacob Ulrich who died young, but his wife Susan Leer remarried and died in Elkhart County. Jacob’s father was Daniel Ulrich (1756-1813) and Susannah Miller (1759-1831) who was the daughter of Philip Jacob Miller and wife Magdalena, ancestors of Hiram’s wife, Eva Miller, which may be the family connection.

This Emanual Whitehead was Eva’s half brother who married an Ulery, and John D. Ulery was married to Eva’s half-sister. This is enough to cause any genealogist to bang their head against the wall.

September 23, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Union – Mr. Violette of Goshen visited with Hiram Ferverda Wednesday.

Sept. 29, 1910 – Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda 1910 Ulery reunion.png]()

Nov. 3, 1910 – Warsaw Daily Times – Mr. and Mrs. Hiram Ferverda spent Sunday with Mr. and Mrs. R. Robinsin (sic) east of Oswego.

Mrs. R. Robinson (actually Robison) was Hiram’s daughter, Chloe.

1911

Feb. 2, 1911 – Warsaw Union – Rolly Robinson and wife spent Sunday with the latter’s parents, Hiram Ferverda and wife, of Leesburg.

Feb. 5, 1911 – Warsaw Daily Union – Andy Vanderford of Whitley County, a former deputy fish and game cop has filed with the auditor of Kosciusko county a bill for $134 for seizing and destroying nets, spears, etc. taken from alleged illegal fishermen during the past 7 years. Cases mentioned include…Hiram Ferverda. Amounts range from 1-10 dollars, in the majority of instances $5.

Hiram must have groaned and rolled his eyes!

Here it is AGAIN!

It. Won’t. Die.

Or maybe by this time it was a big family joke. “Hey Dad, want to go fishing for some bluegills?” Maybe they gave him “nets” for his birthday after his were confiscated.

![Hiram Ferverda 1911.png]()

Mr. and Mrs. John Ferverda of Silver Lake visited with Hiram Ferverda and family over Sunday. John is my grandfather, but my mother and uncle weren’t yet born.

It wasn’t far from Leesburg to Silver Lake – about 18 miles. I wonder if the families had automobiles by then. I’m guessing so.

Attendance Award

May 8, 1911 – Warsaw Daily Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1911 attendance.png]()

I think this was the predecessor of “walked uphill, in the snow, both ways” – except it was true. What an amazing record. School was very important to the Ferverda family – which isn’t surprising given that Hiram’s father, Bauke, was a teacher in the Netherlands.

Hiram Becomes a Marshall

October 19, 1911 – Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda 1911 marshall.png]()

This is the first mention of Hiram being a Marshall which is extremely unusual for a Brethren man. Brethren eschew public office and generally refuse to fight in wars or participate in any other type of activity which conflicts with their pacifist doctrine. Yet, Hiram continued to be Brethren. This must have caused some very interesting conversations!

1912

March 14, 1912 – Northern Indianian – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg, visited n Warsaw on Tuesday.

![Hiram Ferverda Warsaw courthouse back.jpg]()

The courthouse in Warsaw is beautiful from all sides.

March 16, 1912 – Warsaw Daily Times – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg transacted business in Warsaw on Saturday.

March 21, 1912 – Northern Indianian – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg transacted business in Warsaw on Saturday.

I can’t help but wonder what kind of business he was transacting or was this just the stock commentary. He could have been shopping.

May 25, 1912 – Warsaw Daily Times – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg transacted business here (Warsaw) on Saturday.

May 30, 1912 – Northern Indianian – Hiram B. Ferverda of Leesburg transacted business here (Warsaw) on Saturday.

Leesburg to Warsaw was 12 miles and Hiram is going to Warsaw on Saturdays for something, but what, and why Saturday?

Progressive Republicans

June 6, 1912 – Northern Indianian – County Convention Personnel, Second Precinct, H. B. Ferverda

July 26, 1912 – Warsaw Daily Times – The Progressive Republicans of Kosciusko formed a county organization on Thursday afternoon in city hall in Warsaw. Notices were sent to the men who were delegates at the last district convention in Warsaw and asked each to bring friends. When called to order, nearly 60 were present. At the outset, Mr. Vail explained the purpose of the meeting which he said, was to form an organization which could legally send delegates to the state and district conventions of the progressive party for the purpose of naming national delegates to nominate Theodore Roosevelt or some other progressive and for the purpose of selecting progressive national electors. The purpose is to give the voters a chance to express their actual sentiments at the polls in November by having a progressive ticket in the field. After that, various men expressed their opinions, including Hiram Ferverda from Plain Township.

I wish they had recorded the various opinions expressed.

Now, Hiram, a Brethren who is supposed to avoid politics is a “Progressive Republican,” and active to boot!

The Progressive Party was a third party in the US formed in 1912 by former President Theodore Roosevelt after he lost the presidential nomination of the Republican Party to his former protégé, incumbent President William Howard Taft. This party was considered to be center-left and was dissolved in 1918, but in 1912, it was quite the sensation.

Proposals on the platform included restrictions on campaign finance contributions, a reduction of the tariff and the establishment of a social insurance system, an eight-hour workday and women’s suffrage.

In 1916, the conventions of both the Republican and Progressive Republican parties were held in conjunction with each other, with Roosevelt being the nominee of both. He refused the Progressive nomination, accepting the Republican nomination, after which the Progressive Party collapsed.

August 1, 1912 – Northern Indianian – Progressive Republicans Meet in City Hall at Warsaw, Form an Organization, Differ Only On National Issue, No Third County Ticket to be Placed in Field, Nor is Third State Ticket Favored

![Hiram Ferverda 1912 delegate.png]()

Hiram B. Ferverda was present as a delegate.

October 11, 1912 – Mr. and Mrs. John Ferverda of Silver Lake are here for a two weeks visit with his parents, Mr. and Mrs. H.B. Ferverda.

Wow, that’s a long visit.

1913

January 3, 1913 – Warsaw Daily Times – Commissioners allowed Hiram B. Ferverda 56.70 for road repair.

Horseshoes Anyone?

May 17, 1913 – Warsaw Daily Union – An old fashioned game of horseshoe has opened up in town. Games are going all of the time. Hiram Ferverda is champion pitcher.

A horseshoe champion – who knew! I wish there had been pictures. In 1913, Hiram would have been 59 years old.

1914

January 8, 1914 – Warsaw Daily Union – H. B. Ferverda allowed 109.20 for gravel road repair.

January 15, 1914 –- Northern Indianian – H. B. Ferverda allowed 109.20 for gravel road repairs.

January 29, 1914 – Northern Indianian – Plain Township trustee report shows the following disbursements…Hiram Ferverda, labor, $24.

April 2, 1914 – Warsaw Union – H. Ferverda and family were the guests of Bert Frederickson and family on Sunday.

May 6, 1914 – Warsaw Daily Union – Rolin Robison and family and Hiram Ferverda and family were the guests of the latter’s brother, William Ferverda at Nappanee, Sunday.

June 11, 1914 – Northern Indianian – Allowed H. B. Ferverda $5.00 for gravel road repair.

August 13, 1914 – Warsaw Union – the Progressives of Plain Township met Wednesday and elected the following township ticket: Trustee – Hiram Ferverda.

August 21, 1914 – The town council has bucked up against a proposition that is causing the members much worry. At the meeting last week a sidewalk was ordered along the east side of Main Street at the west end of H.B. Ferverda’s property and when Mr. Ferverda went to stretch the line for his walk it was discovered the Winona Interurban station freight house watercloset are all out about 4 feet past the walk line. What action the council will take in the matter is being watched with much interest.

![Hiram Ferverda 1914 watercloset.png]()

Apparently Hiram had public toilets on the west side of his property. Apparently the Winona Interurban lines ran along what is now State Road 15 and the offices, probably pictured here, sat on the west side of Hiram’s land. The automobiles look like 1909 Model Ts, although I’m clearly no expert.

![Winona Interurban an Leesburg]()

The Winona Interurban didn’t last long, being placed into receivership in 1916, so this photo of the “freight house” at Leesburg must have been taken about the time Hiram lived there.

Nov. 12, 1914 – Northern Indianian – Allowed H. B. Ferverda 140.75 for highway repair.

1915

January 28, 1915 – H. B. Ferverda allowed $23.27 for labor for roads.

March 18, 1915 – Warsaw Union – Adopts City Airs – People who visit Leesburg this summer must run their cars up to the curb in an angling position according to instructions issued to Town Marshall, Ferverda.

Angle parking is still in effect in front of the heritage “business district” buildings. Who knew this was a “city air.”

![Hiram Ferverda angle parking.png]()

March 31, 1915 – Warsaw Daily Times – Hiram Ferverda Jr. had the misfortune to badly bruise his finger while playing with a corn sheller.

This would be Hiram’s grandson through his son Irvin and wife Jesse Hartman. Young Hiram would have been about 3.

April 8, 1915 – Northern Indianian – H. B. Ferverda and S. V. Robison and their families visited Rollin Robinson and family Sunday.

May 6, 1915 – H. B. Ferverda and S. V. Robison and their families visited Rollin Robinson and family Sunday.

May 6, 1915 – Warsaw Union – Allowed H. B Ferverda asst road supt. $5.64.

Hiram is noted as the Assistant Road Superintendent.

Marshall Drama

June 7, 1915 – Warsaw Union – Leesburg Marshall Resigns – H. B. Ferverda, marshal of Leesburg, has resigned because the office made too many enemies. He states that many people refuse to speak to him because he did his duty.

Dec. 23, 1915 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1915 Marshall resign.png]()

Hiram was Marshall for 4 years and a few months.

1916

January 7, 1916 –- Warsaw Union – H. B. Ferverda allowed 186.20 for gravel road repair.

Jan 20, 1916 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 tramp.png]()

I find this amusing because Brethren are supposed to avoid physical conflict, which is why they do not participate in wars and historically, would not even defend themselves or their families from frontier attacks. But here Hiram is dealing with a man that “showed fight.”

I wonder if the tramp was sent alone or accompanied.

More Drama – Throws Down Star

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 marshall drama.png]()

I can sense his frustration, even today, 103 years removed.

Jan. 21, 1916 – Warsaw Daily Times – H. B. Ferverda, assnt road supt – allowed $5.64.

No Marshall, By Heck

Not only was this getting juicy, the word was also spreading!

January 24, 1916 – Rochester Sentinel (Fulton Co., Indiana)

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 no marshall by heck.png]()

January 29, 1916 – Warsaw Union – H. B. Ferverda allowed $7.50 labor on roads

Feb. 1, 1916 – Warsaw Daily Times – Calvin Baugher is serving as town marshal of Leesburg. Baugher was chosen by the town board following a meeting on considerable friction. H. B. Ferverda previously held the position.

Feb. 3, 1916 – Warsaw Daily Times – Calvin Baugher has been appointed town marshal by the town council to fill the vacancy made by the resignation of H.B. Ferverda who quit when someone stated at a board meeting that the town did not need a marshal. The job pays $75 per year and the holder is supposed to serve as street commissioner peace officer and several other jobs.

Feb. 5, 1916 – Rochester Sentinel

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 pay.png]()

“Not to pump the water.” That’s just about the only thing the Marshall doesn’t do.

Each of these articles tells the story in a slightly different way, and includes different tidbits of information.

February 10, 1916

![Hiram Ferverda February 1916.png]()

I’m sure that Hiram was just glad to have this entire chapter closed. It sounds miserable and it had to affect his banking business.

The rest of 1916 seemed to be settling down a bit. Maybe Hiram found peace working on the roads.

Feb. 10, 1916 – Northern Indianian – H. B. Ferverda allowed $7.50 for labor on roads.

May 3, 1916 – Kosciusko Union – H. B. Ferverda allowed $20 for repair of gravel road.

Ira Ferverda Saves General Pershing’s Life

May 4, 1916 – Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda Ira saved Gen Pershing.png]()

Hiram must have been very, very proud of his son.

This from the Indianapolis News on May 10th:

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 Ira 2.png]()

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 Ira 3.png]()

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 Ira 4.png]()

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 Ira 5.png]()

This event didn’t happen in 1916, but during the Mexican American War between 1901-1904.

1916 wasn’t going to stay calm for long.

But Then There was that Cow Incident…

May 21, 1916 – Warsaw Union – An affidavit was filed Saturday in the court of Squire Garty by Ola A. Harris against H. B. Ferverda, retired farmer, bank director and business man of Leesburg, charging him with injury and cruelty to animals. Saturday morning when Ferverda and F.J. Filbert of the Leesburg Journal and their wives were driving to this city, they approached the Ola Harris farm two miles west of town. A son of Mr. Harris was herding several cattle which were browsing along the highway. The auto driver, Mr. Ferverda, slowed up and endeavored to get around the cattle, but one Holstein heifer, valued at $100 by Mr. Harris, jumped into the machine and from the contact with the bumper its hind leg was broken, while a lamp on the auto was damaged. Harris demanded $100 of Ferverda in return for the cow, which had to be killed, but the Leesburg gentleman refused any settlement on the ground that he was in no wise to blame. Ferverda and his party drove on to Columbia City after giving Harris their names and addresses and upon reaching town, Ferverda was arrested on the about mentioned charge. He plead not guilty and arranged for a hearing on Friday, June 3. He has employed Levi. R. Stookey of Warsaw to defend him and gave bond for appearance.

Hmmm, interesting to note that there is or was a Leesburg Journal.

We now know that by 1916, Hiram did own an automobile.

May 31, 1916 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 cow trial.png]()

June 3, 1916 – The case of the state of Indiana vs H. B. Ferverda of Leesburg on the charge of injury to animals was tried in the circuit court rooms Friday afternoon by Justice Theordore Garty. Deputy prosecutor Joseph R. Harrison was assisted by attorney D.V. Whiteleather and Ferverda was defended by attorney L. R. Stookey or Warsaw. The defendant was found guilty and fined $10 and costs. An appeal was taken by the defense and the case will be heard in the next circuit court term. Several days ago Mr. Ferverda, a wealthy and prominent citizen of Leesburg, in company with his wife and friends, while driving past the Ola Harris farm, west of town, in an auto, struck a young cow, which later had to be shot on account of a broken leg sustained from the collision. The present case is an outgrowth of a confrontation between Mr. Harris and Mr. Ferverda. Harris claimed Ferverda should pay him $100 damages on the cow and may decide later to file a damage suit.

I think the term “wealthy and prominent” might just say it all about the motivation for this lawsuit.

It’s interesting that Hiram was found at fault for hitting a cow that was in the road. Very different from today.

June 8, 1916 – Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 cow fine.png]()

September 9, 1916 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1916 cow attorney.png]()

I never did discover the outcome.

![Hiram Ferverda courthouse seat.jpg]()

I did, however, discover this vintage seat in the Warsaw courthouse and couldn’t help but wonder if Hiram sat here during one of his many visits, maybe impatiently tapping his toe on the ground.

1917

World War I had begun in 1914, but by 1917, the action in Europe had really heated up.

In January, in violation of international law, Germany declared unrestricted submarine warfare, hoping to starve the British out of the war. The Germans understood that their actions would probably draw the US into the war, but thought the damage to Great Britain would be so devastating that it wouldn’t matter.

According to the Chicago Tribune in a 2016 article, prices had soared. Bread was 20 cents a loaf and flour jumped $3 a barrel. The country came to understand food conservation with “meatless Mondays” and “wheatless Wednesdays.”

A headline in the Indianapolis News on April 10, 1917, told readers “Patriotic Wave is Sweeping Indiana.” The article reported that “thousands of native and foreign-born citizens are showing their fealty to the flag by taking part in great street demonstrations which include parades, salutes to Old Glory and the singing of patriotic songs.”

In April, Hiram’s son, George volunteered.

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 George volunteer.png]()

April 12, 1917 – Warsaw Daily Times

The headlines looked like this:

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 headlines.png]()

That Thursday, the entire county shut down to go to Warsaw.

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 war.png]()

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 war 2.png]()

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 war 3.png]()

George was obviously very inspired.

May 10, 1917 – Warsaw Union – allowed H. B. Ferverda, Sept roads, $14.35.

And still, Hiram works on the roads.

May 10, 1917 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 George enlists.png]()

May 11, 1917 – Warsaw Union – allowed H. B. Ferverda, roads $13.35.

Commencement

Meanwhile, as the President was calling for young men to volunteer for the military, Hiram’s youngest son, Donald, was graduating from high school.

May 22, 1917

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 Donald graduation.png]()

How I would love to hear what Donald’s speech.

Wyoming

June 1, 1917 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 Wyoming.png]()

Hiram and Eva set off for Wyoming. I wonder if they took the train or drove. Trains were a lot more reliable than automobiles at that time.

Ira had married Ada Pearl Frederickson in 1904 and moved to Wyoming sometime between the birth of their son in July of 1907 and the 1910 census.

The wave of patriotism may have been responsible for the surfacing of the General Pershing story once again.

July 9, 1917 – Warsaw Daily Times

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 Ira saves Pershing.png]()

August 9, 1917 – Northern Indianian– Lists of Volunteer troops from Kosciusko County

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 George.png]()

This list confirms that Hiram’s father, Bauke, was known as Baker in the US.

Aug. 23, 1917 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 Wyoming return.png]()

I’d guess that Ira and his wife were just plain homesick and when Hiram, Eva and Treva, Ira’s wife’s sister were preparing to leave – Ira decided to go with them. However, Ira’s health was deteriorating too.

Sept. 10, 1917 – Warsaw Daily Times – Warsaw Boys Off For Fort Benjamin Harrison (list includes) George Ferverda

Dec. 21, 1917 – Warsaw Union – George Ferverda arrived on Friday from Camp Shelby to spend Christmas with relatives.

Dec. 29, 1917 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 all home for Christmas.png]()

I would bet this is when the picture was taken – especially since John Ferverda is without his family in the photo and in this article too.

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 photo.jpg]()

Hiram would have been 63 in December of 1917.

The next photo looks to have been taken at the same time but included the other family members in attendance as well.

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 photo all.jpg]()

There’s a bit of confusion about the house.

![Hiram Ferverda old home place.jpg]()

This could have been the same building, with an extended porch. It’s difficult to tell because it certainly is not the house on the farm and it doesn’t look like the house above. However, whichever of Hiram’s grandchildren that wrote the Ferverda book would surely have known.

In 1917, the second draft registration known as the “Old Man’s Draft” was put into place. Hiram’s brother, William, then age 45, registered.

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 William Fervida registration.png]()

His registration tells us that William has blue eyes and light hair.

![Hiram Ferverda William 2]()

I wish Hiram had registered, but he was beyond the age cutoff. Given that my grandfather, John, had blue eyes, I suspect that Hiram did too.

1918

Feb. 7, 1918 – The Northern Indianian – Hiram Ferverda of Leesburg transacted business at Warsaw on Tuesday.

Feb. 8, 1918 – Warsaw Union – H. B. Ferverda allowed $228 for gravel road repair.

Feb 16, 1918 – Warsaw Union- Mrs. H. B. Ferverda of Leesburg spent Friday in Warsaw on business.

Roscoe Enlists and Marries Without Telling His Parents

![Hiram Ferverda Roscoe enlists.png]()

February 28, 1918 – Friends and relatives here had just learned of the marriage last month of Roscoe Ferverda, son of Mr. and Mrs. H. B. Ferverda of Leesburg and Miss Effie Ringo of North Vernon, Indiana. Mr. Ferverda who was a telegrapher at North Vernon enlisted in the signal corps and just before being called for examination was taken sick with measles. He came home for two weeks and immediately upon his return to North Vernon was examined and sent to the training camp at Vancouver, Washington. The wedding took place while at North Vernon for the examination. The bride is expected here tomorrow for a visit with his parents.

Whoo boy! Not only did Roscoe marry without telling his parents and didn’t tell them for a month, but his bride wasn’t Brethren. Not only that, she was coming to meet his parents alone – and pregnant! Their son, Harold was born on August 5th.

Hiram’s Not a Citizen!

April 27, 1918 – Warsaw Daily Times

![Hiram Ferverda 1917 not citizen.png]()

Imagine Hiram’s surprise to discover that he wasn’t an American.

I should probably have requested his naturalization papers when I was in Warsaw.

Don Ferverda Enlists

June 27, 1918 – Warsaw Union – Don Ferverda son of Mr. and Mrs. H. B. Ferverda and…left on Thursday for Fort Wayne where they expect to enlist in the regulars.

This makes 3 of Hiram and Eva’s sons who have enlisted in WWI, plus Ira who served in the Spanish American War. I can’t help but wonder, as Brethren, how Hiram and Eva felt about this, other than praying for their safe return.

I have been unable to find Donald’s military records.

June 29, 1918 – Don Ferverda, son of Mr. and Mrs. H. B. Ferverda, and James Kohler, son of Mr. and Mrs. W.A. Kohler, of Leesburg, left on Thursday for Fort Wayne where they expect to enlist in the regulars.

October 28, 1918 – Warsaw Union – Among the many patriotic residents of Plain township are three men who each have 3 sons in military service. These men are…George Ferverda who is in France, Donald Ferverda who is at Jefferson Barracks, Mo., and Roscoe Ferverda who is in the Signal corps and located somewhere int the state of Washington, sons of Hiram Ferverda of Leesburg. Ira Ferverda, another son, was a soldier in the Spanish-American war and was responsible for saving the life of a captain who belonged to the same cavalry company as Mr. Ferverda. They were crossing a flooded river when Captain Wiltshire lost his balance and started to sink, but was rescued by Ira Ferverda.

![Hiram Ferverda 1918 George Roscoe Don in uniform.jpg]()

The photo above shows the three Ferverda boys who served in WWI and was brought to the Ferverda reunion held in 2010. Roscoe is seated in the middle, George on the left and Don, at right. I don’t know if this picture was dear to Eva Miller Ferverda or broke her heart that her sons were serving in a war, giving her Brethren heritage and that her grandmother was born in Germany.

1919

April 23, 1919 – Warsaw Daily Times – H. B. Ferverda and wife of Leesburg and Erv Ferverda and family spent Sunday with Ira Ferverda and family.

June 12, 1919 – The Northern Indianaian – Mr. and Mrs. Hiram Ferverda of Leesburg and Mr. and Mrs. John Ulrey of Napanee were guests of Mrs. Sarah Whitehead on Monday afternoon.

June 19, 1919 – Northern Indianian – H. B. Ferverda allowed $12.65 for road repairs

Aug 13, 1919 – Warsaw Daily Times – Rollin Robinson and family, Rosco Ferverda and family, Hiram Ferverda and wife of Leesburg, John Ferverda ad family and Mrs. McCormick of Silver Lake spent Sunday with Lewis Hartman and family.

Mrs. McCormick is John Ferverda’s mother-in-law.

Ladies Aid Society

November 5, 1919 – On Wednesday the Ladies Aid society of the New Salem church met at the home of Mrs. H. B. Ferverda.

I wonder if this meant that Hiram was absent until the meeting was over. Maybe he went to the bank or to see one of his sons. My Dad used to go to the barn or the mill when these “hen gatherings” happened at our house.

This is the first mention of the Ladies Aid Society, and I wonder if it was formed in response to the War effort.

Nov. 12, 1919 – Warsaw Union – Mrs. H. B. Ferverda and Mrs. Thomas Dye, of Leesburg were in Warsaw Wednesday morning enroute for Fort Wayne where they will visit for several days with the former’s daughter, Mrs. Louis Hartman.

This tells us that daughter Gertrude, known as Gertie, had moved to Fort Wayne.

1920

In the 1920 Census, Hiram clearly lives on Church Street – probably in the last house before the census-taker turned the corner and started down Prairie, which runs parallel. This confirms the location of his house.

![Hiram Ferverda 1920 census.png]()

June 11, 1920 – Warsaw Daily Times – B. Ferverda, gravel road repair $13.75

Dec. 21, 1920 – According to the Warsaw Daily Times, Roscoe and his wife were living in Leesburg at this time.

1921

January 19, 1921 – H. B. Ferverda, road work, $17.80.

July 8, 1921 – H. B. Ferverda for gravel road repair $36.42.

Sept 10, 1921 – H. B. Ferverda gravel road repair $20.05.

Oct. 13, 1921 – Roscoe Ferverda, new agent for the Big 4 has moved his family into the Burdge property on Main Street.

The railroad ran parallel to Old 15, on the east side of Leesburg.

1922

Feb. 10, 1922 –- Warsaw Daily Times – H. B. Ferverda grading road $1.75.

Hiram is still grading roads!

May 9, 1922 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1922 bank.png]()

This is the first in a series of bank statements published. I suspect this began in reaction to something – but have no idea what. Hiram is now vice-president. Mr. Hall is still president and has been since the beginning. It’s odd that there are no social interactions between the Hall and Ferverda families.

Donald is now cashier, which I suspect means that he runs the day to day business of the bank.

June 27, 1922 – Warsaw Daily Times – H. B. Ferverda and wife spent Saturday at the David Miller home new New Paris. Mr. Miller, brother to Mrs. Ferverda is in very poor health.

David B. Miller died on September 25, 1922 of chronic kidney disease with bronchitis contributing.

July 3, 1922 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1922 bank 2.png]()

Sept. 20, 1922 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1922 bank 3.png]()

Oct. 13, 1922 – Warsaw Union – Commissioner’s allowances – Hiram Ferverda, gravel road repair – $5

Nov. 16, 1922 – H. Ferverda, C Long Road $72.00.

This is the last road maintenance we find for Hiram. He’s 68 years old.

Dec. 26, 1922 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1922 Christmas.png]()

It’s interesting that they went visiting on Christmas Day. I’m surprised, although many German families actually celebrated Christmas on Christmas Eve, and Eva’s parents were German.

1923

Jan 5, 1923 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1923 bank.png]()

March 30, 1923 – Mr. and Mrs. Ferverda of Leesburg spent Sunday evening with Albert Heckaman and family.

April 9, 1923 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1923 bank 2.png]()

April 30, 1923 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda Whitehead funeral.png]()

Samuel Whitehead was Eva’s half sibling through her mother’s first husband and died of chronic bronchitis.

July 30, 1923 – Warsaw Daily Times and the Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda 1923.png]()

August 21, 1923 – Warsaw Daily Times and the Northern Indianian – The 4th annual reunion of the Hartman family was held August 19th at the home of Pearl Hartman near Larwill, Indiana. At the noon hour, a picnic dinner was served under the trees. A program consisted of music and songs followed the dinner. Games were played and ice cream was served late in the afternoon. There were 119 relatives which came from far and near to enjoy this happy reunion. Present were…(long list including) Mr. and Mrs. Hiram Ferverda of Leesburg.

September 3, 1923 – Warsaw Daily Times – Will Ferverda and family, living north of Gravelton, were Sunday guests of his brother, H. B. Ferverda and wife.

Sept 22, 1923 – Warsaw Daily Times

![Hiram Ferverda 1923 bank 3.png]()

October 3, 1923 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda October 1923.png]()

John’s wife was Edith.

Nov. 10, 1923 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1923 bank 4.png]()

Nov. 12, 1923 – Warsaw Union – Ira Ferverda and family of Oswego expect to move to Leesburg next Monday.

Nov. 22, 1923 – Warsaw Daily Times – Mr. and Mrs. H. B. Ferverda spent Wednesday in the John Ulery home. Mr. Ulery is quite poorly.

1924

January 5. 1924 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1924 bank.png]()

April 11, 1924 – Warsaw Daily Times and the Northern Indianian – Mr. and Mrs. H. B. Ferverda spent Thursday at Silver Lake with their son, John and family.

April 11, 1924 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda Emanual Whitehead funeral.png]()

Eva’s brother Emanuel was 75 years old and died of a stroke.

April 24, 1924 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1924 bank 2.png]()

July 22, 1924 – Warsaw Daily Times – Mr. and Mrs. Roscoe Ferverda and two children of Silver Lake spent Sunday at the home of his parents, H. B. Ferverda and wife.

Sept 23, 1924 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1924 bank 3.png]()

These bank notices stopped at this point.

Sept. 27, 1924 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian – Mrs. George Han?? (possibly Haney) of Milford Junction and Will Ferverda, living near Gravelton were here Friday to see H. B. Ferverda who has been seriously ill for several days.

This is the first indication that Hiram is ill.

October 7, 1924 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda 1924 large family.png]()

Fifty descendants – how amazing!

October 8, 1924 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian – Mrs. Gertrude Dausman returned Tuesday to her home at Nappanee after spending a week here with her brother, H. B. Ferverda.

Looks like the family is all coming to say goodbye.

October 16, 1924 – Warsaw Union – Mr. and Mrs. Roscoe Ferverda were at Leesburg Saturday with the former’s parents.

Dec. 29, 1924 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda 1924 Don cashier.png]()

1925

April 13, 1925 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda 1925 Easter.png]()

I wonder if my grandmother was at home with my mother who may have been ill.

It’s interesting to learn that Easter gathering was a Ferverda tradition.

Hiram’s Death

June 5, 1925 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda death.png]()

That day’s headline:

![Hiram Ferverda heat wave.png]()

Two days later, on the 7th, Hiram died.

June 8, 1925 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda obituary.png]()

The handwriting was on the wall.

June 8, 1925 – Warsaw Daily Times and the Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda death article.png]()

![Hiram Ferverda death article 2.png]()

Hiram had 7 sons, why only 6 as pallbearers? Maybe there was only room for 6 men?

June 9, 1925 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda services.png]()

June 10, 1925 – Warsaw Union

![HIram Ferverda funeral attendee.png]()

June 10, 1925 – Warsaw Daily Times and the Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda funeral.png]()

From the Silver Lake Record, June 11, 1925, Page 1 column 1:

Leesburg Man Dead – H.B. Ferverda, Father of Two Silver Lake Boys Passed Away – Survived by Widow and 11 Children

Sunday afternoon in Leesburg occurred the death of Hiram B. Ferverda following a long illness of tuberculosis.

He had been up and around until only a few days prior to his death and he was here in Silver Lake on Saturday – Decoration Day – visiting with his sons Roscoe and John Ferverda and families.

Mr. Ferverda was past 70 years of age and was born in Holland coming to this country when only about 13 years of age. He and the faithful wife resided on a farm near Leesburg and there they reared 11 children all of whom were at the parental home on Sunday.

Mr. Ferverda is survived by the widow, the children, one brother, two sisters besides many other relatives.

The funeral was held Wednesday at the New Salem Church near Leesburg and interment was made in the church cemetery. The 6 sons acted as pall bearers, which was the father’s request.

This mention of Tuberculosis is very interesting, because Hiram’s son, John contracted TB in the late 1950s. It’s possible for TB to lie dormant for years.

Hiram’s death certificate says he died of heart exhaustion and a contributory cause of chronic bronchitis. He was a retired farmer. Book H-22, page 50, local nu 6. Died in Leesburg. Age 70 years 8 months 16 days.

![Hiram Ferverda death certificate.png]()

The great irony is that after I finished this article, I realized I had completed it on the cold, rainy 94th anniversary of his death.

June 11, 1925 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda 1925 sons called.png]()

They were a little behind.

June 12, 1925 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian

![Hiram Ferverda card.png]()

Hiram’s Will and Estate

June 13, 1925 – Warsaw Union

![Hiram Ferverda estate to widow.png]()

June 18, 1925 – Warsaw Daily Times and Northern Indianian – Roy G. and Donald D. Ferverda have been appointed executors of the estate of Hiram W. Ferverda who died at his home in Leesburg recently.

During a visit to Kosciusko County in May of 2019, I obtained Hiram’s will and estate papers.![Hiram Ferverda will.jpg]() Hiram wrote his will on the 10th of February. Even though he was 70 years old, he probably didn’t believe his death was imminent until that time.

Hiram wrote his will on the 10th of February. Even though he was 70 years old, he probably didn’t believe his death was imminent until that time.

Hiram left everything to Eva, in fee simple, meaning that she in essence could do anything she wanted with this estate, or any portion thereof.

Following Hiram’s will in the will book is an affidavit of death.![Hiram Ferverda affidavit of death.jpg]() Followed by the widow’s election:

Followed by the widow’s election:![Hiram Ferverda widow's election.jpg]() The clerk’s office wasn’t helpful, but the Historical Society was very nice and sent me Hiram’s estate paperwork, beginning with the inventory.

The clerk’s office wasn’t helpful, but the Historical Society was very nice and sent me Hiram’s estate paperwork, beginning with the inventory.

![Hiram Ferverda estate inventory.jpg]()

As expected, Hiram owned stock in the bank. He also had a couple of CDs and some cash.

His “old car” was only worth $50, and I surely wish they had said what kind of car it was. It would be worth far, far more today.

The land Hiram had purchased for $8000 in 1893 had almost doubled in value.

Given that Hiram owned 4 tons of hay, I’d wager that Irv paid his rent in a percentage of crops.

What’s missing is the land Hiram owned in Leesburg. Where is that?

The settlement of Hiram’s estate is shown thus:

![Hiram Ferverda estate settlement.jpg]()

There were crops not inventoried, probably because they hadn’t yet been grown or harvested in June when Hiram died. The inventory was settled more than a year later, in November of 1926.

Hiram’s funeral cost a whopping $700, 14 times more than the value of his car, but his medical care, only $30.

Ironic that the insurance was only on the farm buildings, not the houses, or at least not the house in Leesburg.

John Ferverda’s Debt

It appears that for some reason, in 1924, John Ferverda, Hiram’s son, had fallen on hard times. My mother would have been about 18 months old.

On June 21, 1924, Hiram in essence co-signed for a note for John due to Indiana Loan and Trust in Warsaw for $1600 plus interest, due 60 days later. Why didn’t Hiram do business with his own bank?

On April 11, 1925, Hiram signed for a note for son John for a second note in the amount of $3900 plus interest to People’s Bank, his own bank, due in 6 months.

Apparently neither of these notes was paid by either man. Hiram was clearly gravely ill and John was obviously unable to pay.

By the time the estate settled, the total of John’s notes was $6096.84 – nearly one third of the total value of Hiram’s estate, including Hiram’s farm.

I wondered if John borrowed money to purchase his house, but I believe that they lived in that home when my mother was born in 1922, so that wouldn’t explain the 1924 and 1925 loans. These loans look short term, like they expected to be repaid shortly – but weren’t.

Eva paid those notes in order that the land and other assets not have to be sold in order to pay the balance.

I wonder where she obtained the funds to pay that huge bill.

Louise’s Will

This story isn’t finished, because Louise’s will and estate settlement takes up in early 1940 where Hiram’s story left off. Louise died on December 20, 1939 and her will as probated shortly thereafter – but for the rest of the story, you’ll have to join me for the article “Evaline Louise Miller’s Will, Estate and Legacy,” to be published shortly.

Love Letter from Eva

This love letter from Eva was found in Hiram’s Bible, given to him in 1900.

![Hiram Ferverda 1900 note from Eva]()

In it, Eva says:

“Search the scriptures for in them you shall find eternal life.”

Followed by:

Remember me when this you see,

While traveling o’er life’s troubled sea,

If death our lives should separate,

I pray we’ll meet at the Golden Gate.

Your wife,

Eva

Hiram and Eva Together

![Hiram Ferverda Salem Cemetery.jpg]()

After leaving Hiram and Eva’s farm and property in Leesburg, I drove to the Salem Cemetery, across the road from the New Salem Church of the Brethren to visit them.

Hiram has been residing here for almost 94 years and Eva for almost 80 with three of their sons, Irv, Ray and Don.

![Hiram Ferverda New Salem Church.jpg]()

The creation of this church was reported in the Gospel Messenger, as follows

The Gospel Messenger Feb. 1911 page 92

Bethel congregation met Jan. 28, in 1 special council for the purpose of dividing the congregation into districts. Before this work was taken up. Eld. John Stout and wife, were received by letter, and two were granted. We had with us adjoining elders, Brethren Henry Wysong, James Neff and Amsey Clem. Bro. Wysong officiated. The question of division was taken up and after discussion the vote was taken, which resulted in a line being drawn east and west between the two country churches. Salem and Pleasant View Chapel, thus placing Pleasant View Chapel and the Milford church in the northern congregation still retain in the name of Bethel, Pleasant View Chapel being the mother church. The Salem congregations then decided to meet in council Feb. 9, to effect a new organization. It is our earnest desire that both congregations may be benefited by the change made, and that both may prosper in the cause of the Master.

Hiram and Eva had likely been members at Bethel, formed in 1859.

![Hiram Ferverda Salem gate.jpg]()

Across from the church, wrought iron gates beckon visitors into the cemetery.

![Hiram Ferverda stone and church.jpg]()

I have taken several photos of their stone in order that others can locate their final resting place without walking the entire cemetery![😊]()

Hiram and Eva’s stone is almost directly down the row in front of the gate across from the church.

![Hiram-Ferverda-stone-with-tree.jpg]()

In front of a large pine tree.

![Hiram Ferverda gravestone.jpg]()

Hiram Bauke and Eva Miller Ferverda’s resting place in the New Salem Cemetery, Kosciusko County, Indiana. I wonder if Eva visited often, talking to Hiram, in the 14 years she outlived him.

Based on the estates, I believe the stone was purchased when she died, not when he died. Eva certainly didn’t need a stone to find him.

![Hiram-Ferverda-gravestone-and-me.jpg]()

I’m terrible at selfies, but I couldn’t resist. I felt like I was representing several people that day; my grandfather, John, Mom, her brother, me, my brother and my children.

I also realize that based on how far distant my life is today from this farm crossroads in Indiana, I’m probably also saying goodbye…that is…until I see them all at the Golden Gate.

According to the information from the Ferverda book, this would be the farm near Leesburg. Hiram is holding the baby, and Eva is in the dark dress. My grandfather, John, was on the horse at far right.

According to the information from the Ferverda book, this would be the farm near Leesburg. Hiram is holding the baby, and Eva is in the dark dress. My grandfather, John, was on the horse at far right.

Another antiseptic letter. You’d think a personal visit would have been much more respectful to deliver this type of devastating news.

Another antiseptic letter. You’d think a personal visit would have been much more respectful to deliver this type of devastating news.

Hiram wrote his will on the 10th of February. Even though he was 70 years old, he probably didn’t believe his death was imminent until that time.

Hiram wrote his will on the 10th of February. Even though he was 70 years old, he probably didn’t believe his death was imminent until that time. Followed by the widow’s election:

Followed by the widow’s election: The clerk’s office wasn’t helpful, but the Historical Society was very nice and sent me Hiram’s estate paperwork, beginning with the inventory.

The clerk’s office wasn’t helpful, but the Historical Society was very nice and sent me Hiram’s estate paperwork, beginning with the inventory.

A comparison of the various signatures, assembled by researcher Stevie Hughes some years ago shows us the following variations.

A comparison of the various signatures, assembled by researcher Stevie Hughes some years ago shows us the following variations.